Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT)

Sleeping sickness, also known as human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), has been a dreaded disease for centuries, especially in rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. The cause is a parasite transmitted from human to human by the tsetse fly. Over an average of one to two years, the parasite crosses the blood-brain barrier, after which the patient progressively deteriorates, ultimately dying of the disease an average of three years after infection.

Until about 10 years ago, the treatment was about as feared as the disease itself. Up to 10% percent of patients treated with arsenic-based Melarsoprol died from the side-effects of the drug rather than the disease.

Fortunately, sleeping sickness is much less infectious than e.g. COVID-19 and it is possible to stop the spread of the disease through early detection and treatment of infected individuals. After a major outbreak in the 1930s, the disease was virtually under control by Congo's independence in 1960. When subsequent early detection was neglected, the disease returned – not only in DR Congo, but also in other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that, in the 1990s, the true number of patients was up to 10 times higher than the 25 to 30 thousand cases per year known. This means that hundreds of thousands of people died of the disease. During this period, Belgian support for sleeping sickness control in what was then Zaire had also stalled.

Belgian development co-operation is reinvesting in battling against the disease

Late last century, Belgian development co-operation decided to reinvest in battling the disease, involving NGOs such as Memisa and MSF, the Belgian Technical Co-operation (now Enabel) and the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM).

The results were spectacular and the disease is now back under control. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Congolese National Programme for the Control of Sleeping Sickness was able to screen some two million people annually, with the number of confirmed sleeping sickness cases falling to 400 patients per year.

Since 2014, the ITM has co-ordinated the support of the Belgian development co-operation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to combat sleeping sickness in the DR Congo, where more than 70% of cases are reported. Over the years, the ITM has played an important role in combating sleeping sickness.

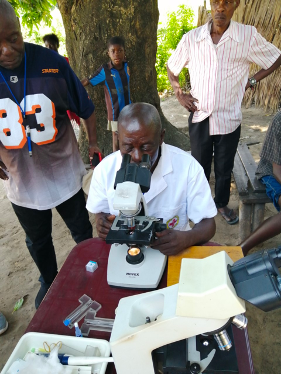

The ITM developed and continues to produce the screening test that has been by far the most widely used for the past 25 years. More recently, rapid tests have also been developed, similar to self-tests for COVID-19. One such test was developed by the Belgian firm Coris Bioconcept in Gembloux, with support from the ITM.

Positive outlook due to new medication and rapid tests

But there is even more good news, which explains why Belgium and BMGF are supporting the eradication of the disease. The oral medication fexinidazole has been available since 2020, so hospitalisation is no longer required for treatment. Acoziborole, a second oral medicine, is in the final stages of development. It can be given as a single dose of three tablets and appears to have few side-effects.

This opens up new opportunities for treating more patients, which should lead to further progress. New rapid tests are making it possible to screen large groups, even where laboratory personnel are absent. If we then have a safe medicine on top of that, we can treat people with a positive rapid test immediately, without complex testing to detect the parasite itself.

Meanwhile, the ITM has developed some other tests, including a PCR test, which can be performed retrospectively on a blood sample in the lab to see whether the parasite is still circulating. Along with the ITM, the Turnhout-based company APDia has developed a better-performing serological test that it hopes will play an important role in the future.

Digital data management – a key asset

The DR Congo has always been the hardest-hit country over the years, but the situation now is substantially different than it has been in the past. Not only have diagnosis and treatment been thoroughly improved, but digital data management is also a key asset, allowing for better planning of diagnosis and treatment. Partner institutes from Liverpool and Montpellier have also developed some new methods for controlling the tsetse fly, which is a further asset.

All these innovations explain how the WHO's strategy is constantly being adjusted, with the results from the DR Congo having a significant impact. The battle against sleeping sickness will have to be won in Congo. Expansion to other countries will be essential in order to permanently eradicate the disease, and progress is being made there as well. In short, the eradication of sleeping sickness is indeed a few steps closer and no longer a distant dream.